Jim Copp, The Forgotten Virtuoso of Children’s Story Telling

By David Owen

This article originally appeared in The New Yorker, 12/12/18

When my wife was a kid, in the early nineteen-sixties, she and her siblings listened, over and over, to records by Jim Copp. I knew nothing about him until thirty years later, when her brother copied a few of the old LPs onto cassette tapes and sent them to us. We played them for our kids, who also loved them, and now our granddaughter, who is five, plays Copp CDs for herself and her friends. And my wife and I still listen to them ourselves, in our cars, when no kids are around.

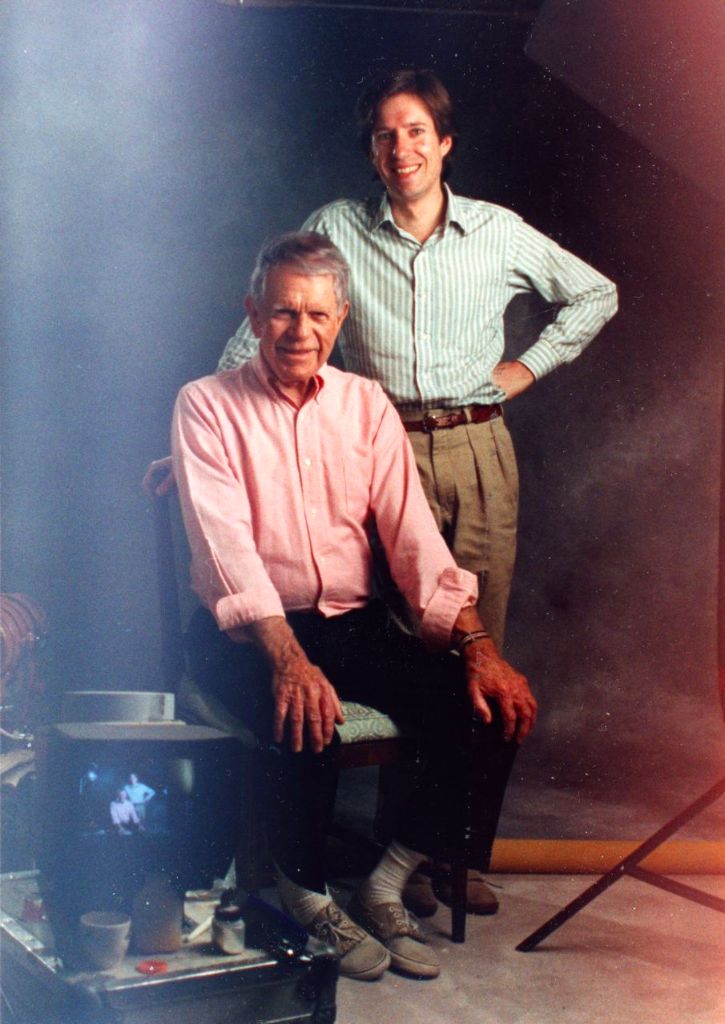

Copp made nine records between 1958 and 1971. They contain stories, poems, and songs that he wrote, performed, and recorded with the help of his friend Ed Brown. The records are literate and funny without ever being arch or patronizing. In stories called “Incident in the Forest” and “The Wedding,” for instance, Copp retells the fable of the lion and the mouse. As in Aesop, the lion spares the life of the mouse, and the mouse repays the lion by freeing him from a hunter’s trap—but then the lion offers the mouse a reward of his choice, and, Copp says, “Instead of picking something proper for him, like a supply of cheese or a new house, he replied, ‘I want to marry your daughter, the lioness.’ ” The lion is saddened to think of his daughter as the wife of a “miserable mouse,” but he hides his disappointment, and keeps his promise. During the ceremony, though, the organist, a mole, falters while playing the wedding march, and the lioness trips and (very audibly) squishes the mouse. The lion, not quite concealing his relief, announces that the wedding must be cancelled. “But no reason not to have the party,” he continues. “Everybody dance!” As the revelry begins, he adds, “Somebody sweep up that mouse.” The moral, according to Copp, is that one should never ask for more than one deserves. Jim Copp (right) made recordings that offered children funny fables replete with sound effects, and were literate and charming enough for adults.

Other stories involve a family that takes a cross-country car trip with a cow; a duck that, with excruciating effort, manages to speak just enough English to warn his housemate, a carpenter, that their kitchen is on fire; the longest name in the world who goes to Yale; an inch-tall girl who is abandoned by her parents, adopted by a tin pan, abducted by a toad, and cruelly deceived by a frying pancake; a hen with a low I.Q., in a verse retelling of the Chicken Little story; parents leave him locked in the attic while they go on a Caribbean cruise; a nearsighted heron; and a feebleminded old man, Mr. Hippity, who thinks his chicken pull toy is sick. Copp may be the reason that my wife and her siblings and both our children have always had good vocabularies: destitute, vituperative, locality, inauspicious, gauche, megalomaniac, union suit. My favorite piece—and Copp’s, too, I found out later—is “Cloudy Afternoon,” a long poem about a little boy who, after his nanny has fallen asleep on a bench, rides his tricycle alone through a park and is nearly run over by a bus.

Not long after my wife received the tapes from her brother, she noticed a tiny advertisement in The New Yorker for rereleases of Copp’s records, on cassette. She called the telephone number in the ad, and eventually realized that the person taking her order was Copp himself. I called, too, and, in 1993, I visited Copp in his home when I happened to be in Los Angeles and went to lunch with him at his beach club, in Santa Monica. I learned that he’d been born in 1913, and that when he was fourteen he was invited to play a Mozart concerto with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. (He backed out at the last moment, in a panic, and his father told his mother to let him spend more time outside. He never took another piano lesson.) He edited the humor magazine at Stanford and performed in student musicals, then went to graduate school, in English, at Harvard, where he studied with the poet Robert Hillyer. In 1939, friends whom he was visiting in Chicago dared him to enter a talent contest at the old Edgewater Beach Hotel, whose ballroom was popular with movie stars and mobsters. He performed several humorous pieces that he’d written as a student—“Arabella and the Water Tank,” “Peaches and Myrtle” (about two showgirls, one of whom murders the other), “The Mystery of the Revolving Tree Trunk”—and won.

His prize was a week’s engagement in the same ballroom. When the week was over, the bandleader Will Osborne, whose orchestra famously included unusually many trombones and slide trumpets, offered him a contract, and they headed east. Copp got hooked on performing. During the next three years, he appeared, as James Copp III and His Things, in some of Manhattan’s most famous night spots, among them the Blue Angel, Le Ruban Bleu, the Rainbow Room, and Café Society (both uptown and downtown). “Did you ever hear of Dwight Fiske?” he asked me. “Well, he did risqué things at the piano before I ever came along, and people would book me as ‘the nicer people’s Dwight Fiske.’ Which I didn’t like, and Dwight Fiske didn’t like.” Copp wore gray tweed suits, from Brooks Brothers, and tiny bow ties, which he had custom-made at F. R. Tripler. Much of his act was improvised. At one time or another, he shared billing with Billie Holiday, Lena Horne, Pete Johnson, Hazel Scott, Art Tatum, and Teddy Wilson, all of whom he got to know. Wilson invited him to join a jam session, on piano, but he was too nervous to do it; the owner of Café Society warned him to stay away from Billie Holiday, who, Copp told me, would disappear for several nights in a row, “then come back with a black eye or maybe a broken jaw or something.” In 1941, Liberty released six of his night club pieces, on a set of three 78s.

He was drafted a year later, and became the adjutant of an intelligence unit that took part in the Normandy invasion. “We were breaking codes and listening to Luftwaffe pilots, things like that,” he said. “Nobody knew what we were doing, and we didn’t know what we were doing.” During the liberation of Paris, he and another officer took command of the Eiffel Tower, which provided a conveniently tall base for their radio antenna. He returned to the United States in 1946, but decided that New York and its night clubs had changed in ways he didn’t like. He moved back to California and spent several years writing a society column, “Skylarking with James Copp,” for the Los Angeles Times. He discovered, by accident, that Liberty had been selling his album without paying him royalties, and he got the rights back. At one of the fancy parties that he was covering for his column, he met Ed Brown, who was a few years younger and was working at a steel company owned by his father. Like Copp, Brown was tall, handsome, charming, smart, and funny, and they were often spoken of as two of the city’s most eligible bachelors. In fact, before long, they were a couple.

Copp decided that his best chance of preserving his night-club material was to rework it, slightly, for children. He experimented with a wire recorder—a tape precursor, which recorded magnetically on steel wire. He sold one piece, “The Noisy Eater,” to Capitol Records, which Jerry Lewis recorded, in 1952 (and butchered, in my opinion). Capitol wasn’t interested in Copp as a performer, so he decided that from then on he would make his own records. He bought three Ampex monaural tape recorders and an expensive microphone, and he achieved the equivalent of multitrack recording by “pingponging”: he would record a single character or instrument or effect on one machine, then play that tape in the background as he recorded another on one of the others. For some pieces, he ping-ponged as many as ninety layers. He sped up some voices and slowed down others, all without fancy equipment, and he added homemade sound effects.

He also played all the instruments: autoharp, kazoo, celeste, bongo drums, castanets, tambourine, three-octave pump organ. In “Miss Goggins and the Gorilla,” more than a dozen fourth graders sing a song about a dog named Mr. Jiggs—brilliantly off-key, out of tune, and out of tempo, while their teacher accompanies them on a piano and yells at them—every voice and sound effect you hear is actually performed by Copp, who’s also playing the piano. The guitarist Henry Kaiser, who first listened to Copp’s records at around the time my wife and her siblings did, once saw Copp’s master tapes and said that they consisted of “thousands and thousands of tiny fragments of tape carefully spliced together.” He called Copp an “unsung genius” who “achieved miraculous results with minimal equipment.” (The first real multitrack recorder, which laid down eight tracks on one-inch tape, was introduced by Ampex in 1957. The first sale, for ten thousand dollars, was to Les Paul and Mary Ford.)

Brown, at Copp’s suggestion, quit his job at the steel company in order to help with the records. At first, Copp insisted on doing all the voices himself, but after they’d made one record Brown said that he wouldn’t work on others if he couldn’t perform, too. From then on, Copp wrote parts for him— including “Mr. Brown,” an impish and slightly credulous Irish sidekick for “Mr. Copp.” Brown also helped with the recording, most of which they did in the house that Copp had grown up in, and in which he now lived with his father. (His mother had died, suddenly, a few years earlier, immediately after Thanksgiving dinner.) To create the sound of a woodland stream, Copp told me, they first tried running water in the bathtub. “But that sounded terrible, and you could hear the water in the pipes,” he said. “So I ran a hose up from the front yard and through a bedroom window and into the bathroom. That didn’t sound like a stream, either, so Ed and I went out and dug up a lot of rocks, and put them in the bathtub, and ran the hose over them, and that finally did it.” They often recorded their own parts while standing at the kitchen sink, because Copp liked the mild reverberation from the ceramic tiles. When he needed a fire, he built it in the shower. One of my favorite effects is the sad, hesitant, squawky meandering of Mr. Hippity’s chicken pull toy, which somehow tells you everything there is to know about Mr. Hippity.

Among Brown’s contributions were the inventive LP covers, all of which he designed, and the marketing of the records, which Copp hated doing. When each new album was ready, they travelled around the country visiting department stores, signing autographs, and giving interviews, and at the end of each Christmas-shopping season they took a trip to Hawaii, where they eventually bought property. Copp’s father died in 1971. His sister insisted on selling the house, so Copp moved in with Brown. He also stopped making records. He told me that, by that point, he was tired of recording, and that his equipment was just about worn out, and that, besides, he didn’t like the acoustics of Brown’s house, which was carpeted. Then Brown died, too, in 1978, of pancreatic cancer.

In 1971, Copp had told all the stores that carried their records that he and Brown were now out of business, although he continued to sell down his inventory of LPs, by mail. In 1991, Ted Leyhe, a videographer who had grown up listening to the records, in the early sixties, in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, tracked him down through a connection at a music store. He persuaded Copp to allow him to make a documentary about him—“Skylarking: The Life and Times of Jim Copp”—and to let him rerelease all the old records on cassette and, later, on CD. When Copp died, in 1999, of emphysema, Leyhe and his wife, Laura, became the proprietors of Copp and Brown’s old label, Playhouse Records. Through the label’s Web site, they continue to sell all the original recordings, which they meticulously remastered. They also sell a greatest-hits compilation, “Agnes Mouthwash and Friends,” which includes two nightclub routines that never made it onto the children’s records, and a lovely children’s book-and-CD combination, “Jim Copp, Will You Tell Me A Story?,” illustrated by Lindsay duPont. So Copp’s achievement endures. The Playhouse Web site also contains excerpts from an extensive archive of fan letters, among them one that was sent to Copp by a woman in Croton, New York: “I really do believe that if my house was on fire, one of the first things I would run out with would be our set of your records.”